The Evolution of a Multi-Species Grazing Operation

The Goal of Big Spring Farm:

“An easily managed, low input grazing operation that improves production and the environment while being consistently profitable” Greg Brann.

Brief History of Big Spring Farm 2005: The Big Spring Farm is named for a boiling cold spring that is estimated to have an output of 30,000 gallons per minute. The farm was purchased by my dad in 1964 for cow-calf and trout production, unfortunately, the trout enterprise never materialized. The farm increased in size due to land purchases and land rentals to 1200+ acres of pasture and hay. Over the years, tobacco, Christmas trees, corn, and soybeans have all been produced but it has always been predominantly a cow-calf operation. The largest number of cattle was 300+ cows and 270 backgrounding stocker calves. Dads’ famous sayings were “good pasture is the best fence” and “don’t fix it too good they can’t get back in” and while he did pretty well at maintaining some single wire electric cross fence, the perimeter fence steadily rusted away. At 88, my brother and I are slowly taking over the running of the operation. Currently, my brother and I have divided up the operation and entered some land in CREP, a state form of CRP, leaving my operation with 210 acres of pasture.

Fencing: My brother and I decided we had to have a good perimeter fence above all so that became a priority. With all the blackberry briars, buckbrush, and assorted browse, goats seemed to be a choice species for us. Since we always preferred high tensile fence, what is the big deal about adding an extra wire or two to run goats too? We didn’t know much about goats but I knew it was accepted knowledge that a producer can run 1-2 goats for every cow and not impact the cows grazing. Later we found it actually improved grazing for the cattle. After about one year my brother decided he had had enough of goats dying (Listeria and various other adaptation disorders) and wrestling to de-worm them and trim feet, so I bought him out and continued the goat enterprise. Thankfully, he didn’t charge me any rent since he knew that running them on the correct pastures would control weeds. Later we divided up the land and now he and his sons run stocker cattle and I run a multi-species grazing operation.

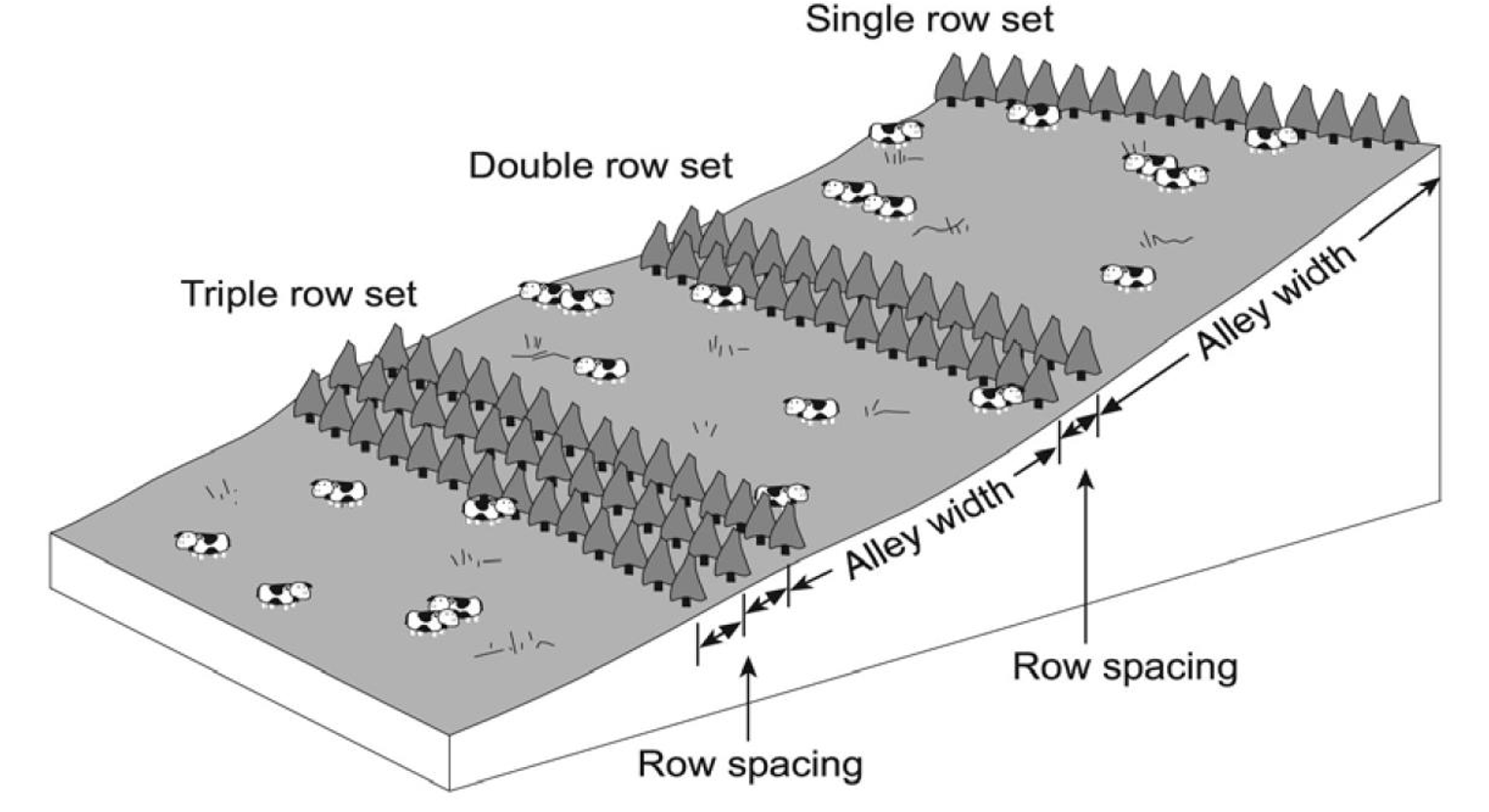

With any new enterprise, you go through an adaptation trough phase for 3 to 5 years before you reach a new plateau for the enterprise. Initially, we just fenced the perimeter of one area and used electro-net fencing to control graze about an acre at a time with a stock density of 7,000 lb/ac. This worked pretty well. We would set up two paddocks at a time and when they moved into the second paddock we would move three sides of the first paddock and set up a third paddock hopscotching across the field. Other areas we fenced were the boundary of fields allowing the goats access to the whole field while cattle were control-grazed.

The ideal fence and water layout are parallel fences about 435’ apart with water hookups located 435’ apart in every other fence line. This allows maximum flexibility. I like 435’ because a 100’ length equals one acre. Three rolls of electro-net 164’ each will more than span this width and if you are using single polywire with a post spacing of 40’ you can easily carry 8 to 10 posts. When I run a high single polywire for cattle (48” high) I space post up to 100’ apart. In the end, when terrain, woods, soil type, and vegetation are all considered spacing between parallel fences may need to vary considerably. Any distance you are willing to walk and install temporary fence is just fine. Initially, you may want to install every other fence with the ultimate goal of installing others later. Not every fence needs to be worthy of controlling all species. When wire is closer to the ground try to target 7” with post spacing needs to be closer usually 40’ works even in rolling terrain. In one year, counting all of the temporary fences built, we have over 50 paddocks.

Creep grazing: Now we run one herd consisting of cows, calves, sheep, lambs, does, kids, a donkey, and five guardian dogs. It’s rather entertaining to watch the herd dynamics. I have eleven permanent paddocks to control all animals and we run a high single polywire holding the cows back and allowing the calves, sheep, and goats to creep graze, and in winter creep hay. This allows creeped animal’s access to more choice thereby increasing nutrition. At other times, I run another low polywire which restricts calves and allowing sheep and goat to graze. This is only necessary when sheep and goats need higher nutrition, such as at breeding or birthing time. It’s also used to keep cows and calves out of sericea hay or high dollar sheep mineral.

Goats to Sheep: Compared to cattle, goats are quite inexpensive, and improving genetics is more difficult when the initial cost of the animal is higher and the gestation period is longer.

Once you are fenced for goats you can run pretty much any species. I monitor forage and pressure continuously for recovery needed to improve forage management. So, I constantly adjust the number of cattle, sheep, and goats relative to what is best for the pasture and animals. Goat numbers at Big Spring Farm fluctuated from 70 to 300 back down to 70, up to 130, and has now settled at around 50 does (Kiko/Spanish nannies). My reasoning for the downsizing is that, even though the goats are extremely prolific and easy to keep, I found the goats compete with the sheep (Katahdin) for forage.

In my experience, sheep compete more with cattle for forage but they are also more productive than goats and cattle and easier to handle. The bottom line for me is that adult ewes over one-year-old rarely need deworming, Katahdin sheep can be bred at 10 months of age and have lambs unassisted after just five months of gestation. Sheep have a higher twining percentage of 1.7 lambs per ewe, whereas the goats only average 1.4 kids per doe. I’ve found that sheep typically don’t eat much hay till all the grazing is over, which is a good thing, but, be careful, they will overgraze if not rotated often.

Cattle to sheep: I’ve been decreasing the cow herd since I’ve found sheep to be so much more productive per female. I don’t know of any other animal that can wean more than their weight in 10 months. Cattle are doing well if they wean 45% of their weight but sheep will wean 100% or more of their weight. The sheep and goats naturally wean their lambs, which creates much less stress for me and the animals. In the past, we had the most problems during weaning lambs and kids. Most of the issues have disappeared now that we allow them to self-wean, eliminating stress for us all. If I was lambing more frequently I would certainly need to wean to maintain ewe condition. If I have one ewe that doesn’t maintain condition due to longer lactation I will likely cull her since she doesn’t fit the herd management.

Due to the stress involved, I am trying to not wean calves either but since cattle lactate longer it makes it much harder. We are selecting for natural weaning cows but still wanting to see the calf weigh at least 45% or more of the cow’s weight when it is ten months of age.

One group versus separate groups: Although I have run the goats and sheep together without incident, I’ve resisted combining the sheep with the cattle due to the inconclusive information regarding the tolerance of Katahdin sheep to copper. After visiting with several sheep producers who have fed beef mineral to Katahdin sheep for 5 years or more I decided to take the chance. It is important to note that wool sheep seem to be more sensitive to copper toxicity than hair sheep.

One huge advantage of running separate groups is you can target graze certain plants. However, the benefits of running one group far outweigh the advantage of target grazing. Target grazing can still be done but you must consider the impact on other animals in the herd. Some call it a flerd; part flock, part herd.

Longer rest periods for pasture (which reduces internal parasite load), being able to feed guardian dogs at one location, hay feeding in one location, more power on less fence, less fence to check, higher stock density for shorter periods of time are all benefits of the flerd system.

Separate herds: In the past, I always maintained a “sell lot” for anything that was not performing up to the standard of the herd. Since we don’t want any births occurring in mid-December through mid-February the rams and bucks are pulled July 24 through September 24. Bulls are just left in with the herd and I pregnancy test in November or December and sell all cows not bred or bred out of sync with the group. The target is a 60 day calving period. Calves are kept till 24 months old and sold as grass-finished cattle. Heifers that don’t breed are still worth a premium as finished cattle.

Watering Facilities: Water is the most important nutrient and is a major draw for the location of cattle. Sheep and goats don’t tend to hang around water the same as cattle do. The tendency is for the pasture around the water point to be overgrazed, partially due to allowing back grazing for more than 4 days.

I am a big believer in a pressurized water system so that you can place the water point where you want it and not be dependent on a good pond site, gravity flow, spring flow, or limitations of ram pump, solar pump, etc. The ideal spot for a water trough is based on rotation, forages, and lay of the land. In general, I want the watering point to be located on a slight slope of 3% grade near the ridge top but mainly you want your to have water throughout the property so that no water point is overgrazed

I have ball waters, ( Richie and Mirofount), tire troughs, open goat troughs, rubber maid portable troughs, and old protein tubes plumbed. I prefer the Gallagher brass valve for open troughs. I like the Mirofount more than the Richie for cattle due to the visibility of balls and the option to take off covers with plumbing still covered. However, the balls are harder to push down on the Miirafount. Balls in either trough can be taken out. Goats and sheep don’t have the power to push balls down like cattle. The ball troughs are lower maintenance than other troughs but more expensive. I mainly have tire troughs throughout the farm. They’re great for big herds but I have lost several goat kids and lambs in the open troughs due to not having the water level high enough. The water must be within 2” of the top. You’ll need to place blocks in water deeper than 12”.

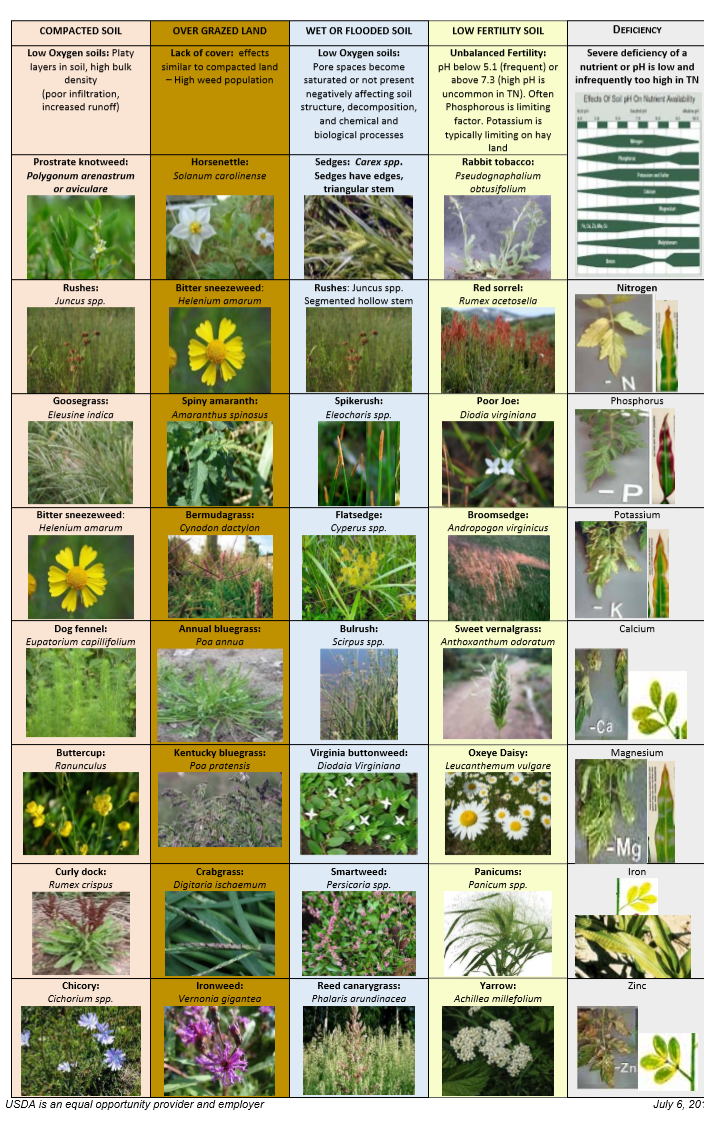

Forage: In general I believe in managing the forage you have and not completely reseeding the entire pasture. A good start is taking a soil test to know the status of soil fertility. If fertilizer dollars are limited, apply lime and fertilizer to low testing soils first. Also, consider the most potential is productions on the best soil types. Get a soil map from the USDA/NRCS office or www.websoilsurvey.com.

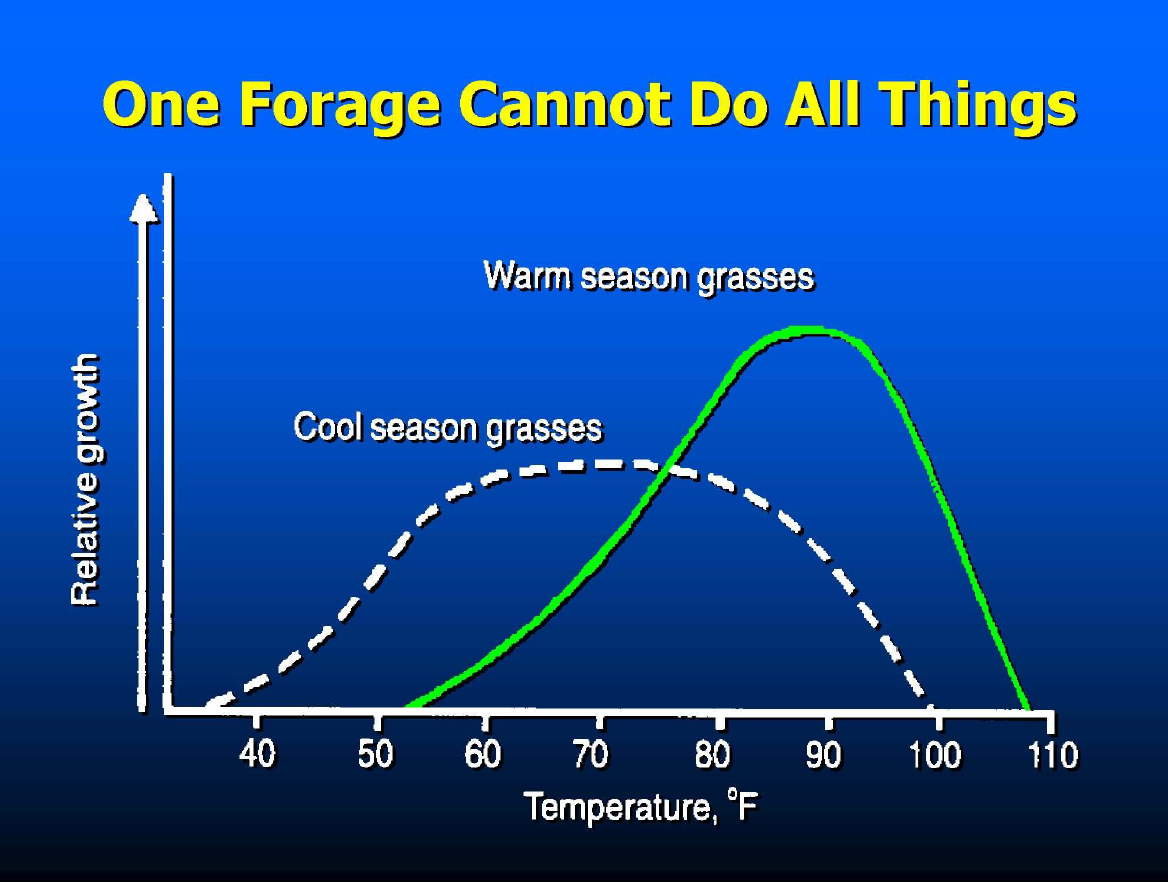

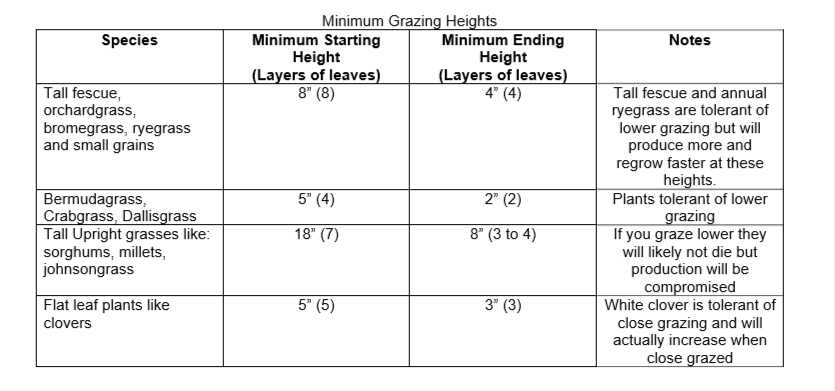

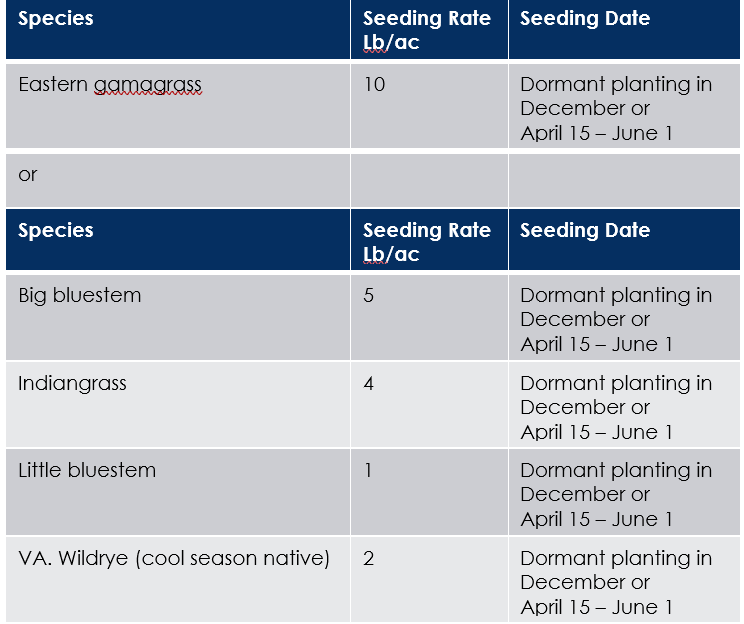

When it comes to seeding mixtures, there are so many choices; cool and warm season, annuals and perennials, grasses, legumes, brassicas, and other forbs and browse. Ultimately its good to have about 30% of the acreage in warm-season forage. First evaluate if your stand of grass is adequate, for cools season grass you need a plant every 6” with 3 strong tillers. If you don’t have this you will need to seed grass as well with a no-till drill or some tillage. The easiest and cheapest way to upgrade the pasture is by adding legumes through frost seeding. There are many advantages to having legumes: higher quality forage, provide nitrogen, lengthening of the growing season. The negative aspects of legumes of over 35% are that it can create voids in a drought. Although white clover is the cheapest, only costing 7-$10/ac to seed at 2 lb/ac I would recommend seeding 4 to 7 lb of red clover/ac. On the most droughty land seed annual lespedeza 8 or more lbs per ac. Lespedeza has concentrated tannins in them and are natural dewormers. Annual crabgrass is an annual that can fill these voids, providing warm-season forage. Crabgrass is a reseeding annual that is a savior but the negative side is it needs disturbance from tillage or high animal traffic at least once a year to maintain vibrancy. Native grasses have great potential but they are slow to establish (approximately 2 years) and do not tolerate close grazing. Bermudagrass is not preferred forage of goats but is excellent around heavy use areas such as corrals or water points. Common bermudagrass spreads by seed, rhizomes, and stolons so it spreads more than hybrid types that very few viable seeds, making the hybrid types vegetatively preferable. Another thing to consider in the evaluation of fields is certain plants that increase due to avoidance by livestock so they are left to reach their full expression and make seed while other plants decrease due to overgrazing and excessive use. Putting pressure on plants you want to decrease especially when emerging and when they make seed are major tools to use to improve pastures while resting or allowing full recovery of plants you want to increase can bring change your pastures quickly.

Hay: Buying hay is always a good deal since the cost of making hay is so high. The average cost of making hay is $80/ton. Also when you bring hay onto your farm you are bringing in nutrients. Each ton of hay, on average, contains 45 lb N, 12 lb P2O5, and 45 lb K2O or $50/ton in nutrients. The key is getting those nutrients deposited by the livestock well distributed over the field. When manure is deposited in the barn, rather than directly on the pastures, the expense of equipment, time, and fuel to load and spread the manure change the economics drastically. Also, remember that when nutrients end up near water they can cause water quality issues.

Summary: Every time I enter a field I evaluate the impacts and improvements of management and determine what is needed to improve the economics, environment, and community dynamics of the operation. Mostly, working with nature is rewarding and humbling.