Living in mud creates an unhealthy environment for a horse. Mud harbors bacteria and fungal organisms which cause diseases such as abscesses, scratches, rain scald, and thrush. Mud is also a breeding ground for insects, especially filth flies. Insects are annoying at best and at worse carry diseases, bite, and can cause allergic reactions. If horses are fed on muddy ground they can ingest dirt or sand particles with hay. This can lead to sand colic, a very serious digestive disorder. Standing in mud can lower body temperature, causing unthriftyness and even hypothermia. In summer the temperature on unvegetated soil can be 9 degrees F hotter than vegetated land. Mud also creates a slick, unsafe footing which can cause slips and injuries for both horses and humans. Due to the weight of horses, their habits, and the closeness of grazing, paddocks can easily be overgrazed and when soils are saturated, vegetation is easily mudded out.

The first step in reducing mud (organic matter and water) is management of surface runoff from roofs, roads and the watershed in general. Locate structures and facilities on well drained areas away from drainage ways and sensitive areas. Locate facilities (barns, shade, water, feed areas, etc) so runoff doesn’t directly enter any water bodies (ponds, streams, intermittent streams, wetlands, sinkholes, depression areas, well heads, etc.). Typically guttering, dips in road, grassed waterways, and diversions, will address most runoff problems. Tile drainage can be used for saturated soils if the area is not a “wetland”.

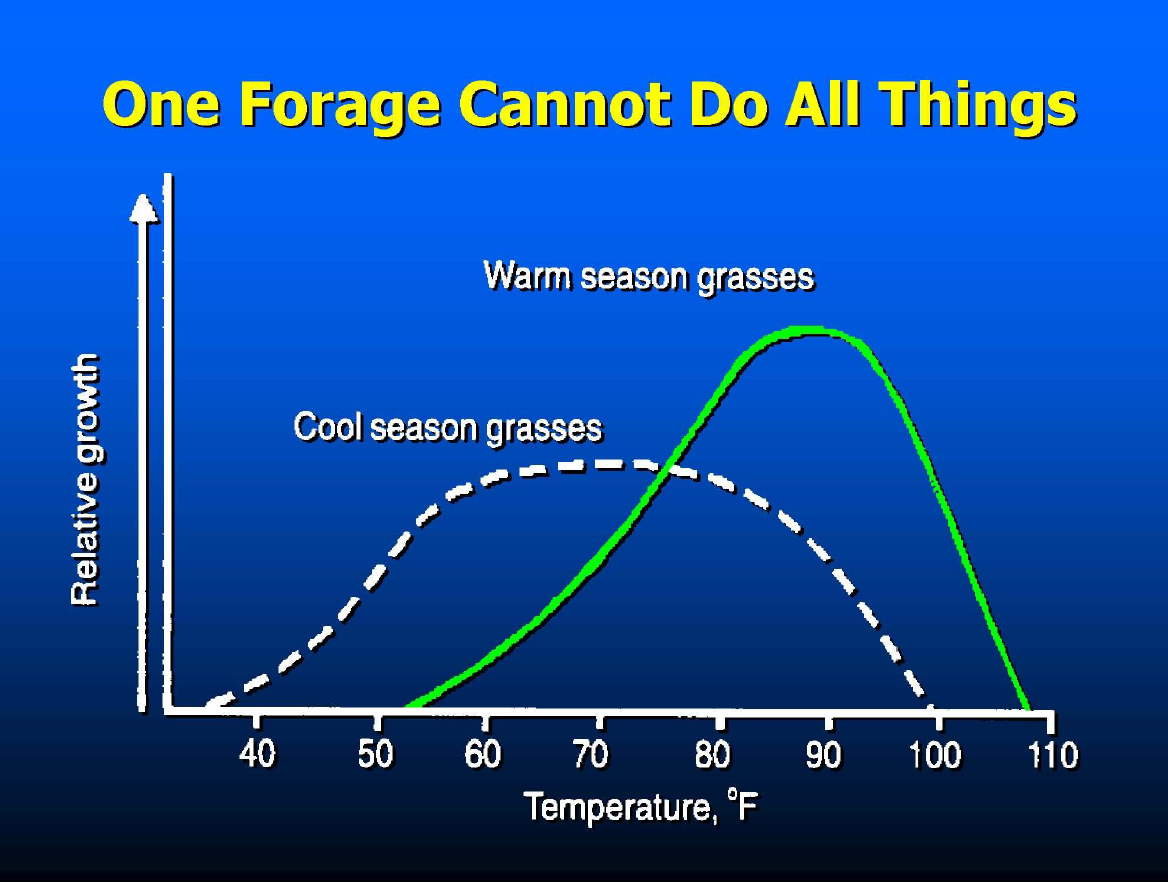

Vegetation: It is the nature of a horse to graze continuously and to graze close. Horses prefer grasses over other vegetation types. Good vegetation management begins with having an alternative place for horses off of the grass when the vegetation is vulnerable to damage. Vegetation should be grazed no closer than 3” for tall fescue and 2” for bermudagrass. Start grazing when grass is 5” to 8” tall. Begin grazing time gradually- too much pasture can cause serious problems. Start grazing about an hour at a time and work up to several hours over a period of weeks. Ideally paddocks would be established in the turf grasses tall fescue and bermudagrass. Tall fescue has the longest growing season and bermudagrass is the most resilient. Generally these will be present in separate paddocks with 30% of the paddocks being bermudagrass. Stockpile grass on some of the paddocks for use during dormant periods (drought or cold). When soils are saturated horses need to be off of the paddocks. A stall can serve this purpose but most horse owners prefer to have horses outside for at least a couple of hours three or more times a week.

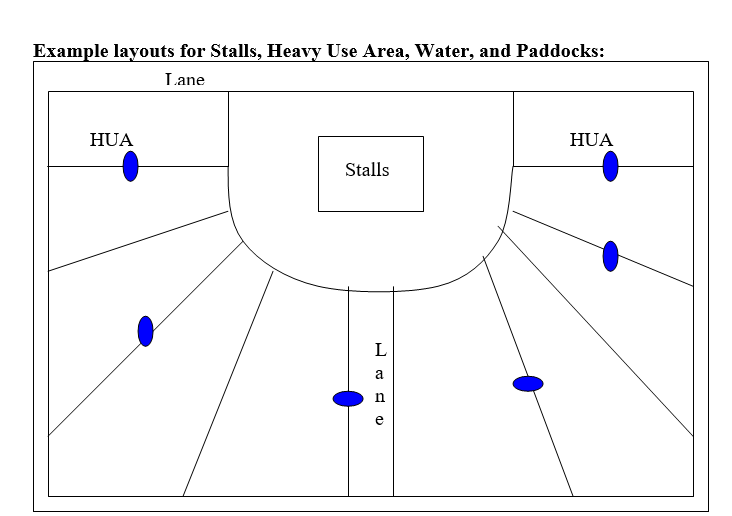

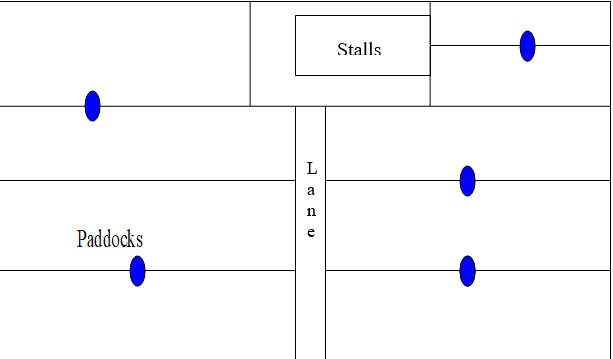

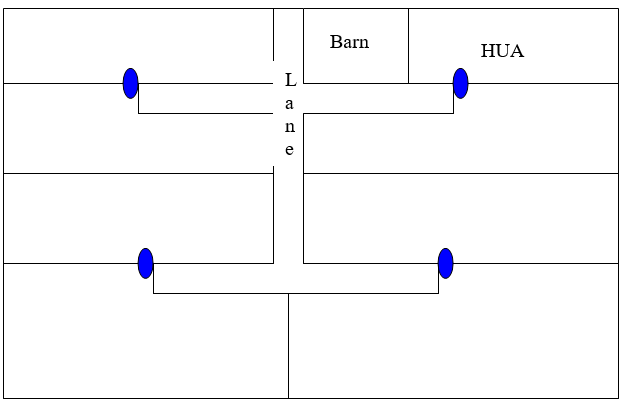

Heavy Use Area: A small heavy use area surfaced with rock (3/8” diameter or smaller) is recommended for exercise and protecting grass paddocks. The recommended size of an exercise lot (heavy use area) depends on the horse’s nature, exercise, and age. The size of the heavy use area can vary from 16’ x 16’ area to a long, narrow enclosure (20’ or 30’ wide by 100 feet) where the horse could actually trot or even gallop. The exercise area could be used by multiple horses at different times. The heavy use area would be best located central to all of the paddocks. Typically it is best to have facilities such as water, mineral, shade, and feed separated for animal distribution. In this case since the paddocks are small placing water and shade on the same heavy use area will keep the cost down and get maximum use from the heavy use area.

Fencing: Choose the safest fencing you can for your sacrifice area and paddocks. Horses are hard on fences however, they tend to respect electric fencing. Best if perimeter fence of paddocks is equivalent to a 5 wire or more high tensile electric fence and interior fence is polytape. White coated high tensile wire is more visible than high tensile wire. Some owners report problems with high tensile wire cutting horses. If polytape is slightly twisted it will shake less in the wind. The minimum recommended size for paddocks is 0.4 ac/horse (1.2 ac{0.4 x 3 paddocks}/horse). A minimum of 2 gates should be installed so gates can be rested, reseeded, and etc. Locate gates for optimum use and flexibility in dividing up paddocks. Grouping horses will reduce management and cost.

Paddocks:

Alternative 1 (Horses provided full feed): In addition to the stall and heavy use area it’s recommended to have a minimum of two grassed paddocks. 0.4 ac/ paddock x 2 = 0.8 ac/ horse. Example: 5 horses = two 2ac paddocks 4 acres total needed in addition to stalls and heavy use area. .

Alternative 2 (Horses provided 2/3 to full feed): If no stall is used a minimum of a heavy use area is needed with three paddocks. 0.4 ac/ paddocks x 3 = 1.2 ac/horse. Example: 5 horses = three 2ac paddocks 6 acres total needed in addition to a heavy use area.

Alternative 3: No stall or heavy use area (Approximately one ton of hay would need to be fed per horse): If no stall or heavy use area is used to control horse access to paddocks a minimum of 3 paddocks are needed with a minimum of 0.8 to 1.0 acres/paddock, = 2.5 to 3.0 acres/horse. Rotate horses to maintain vegetation on the paddocks and allow fields to rest and recover after grazing. Example: 5 horses = three 5ac paddocks. Total acres needed = 15acres.