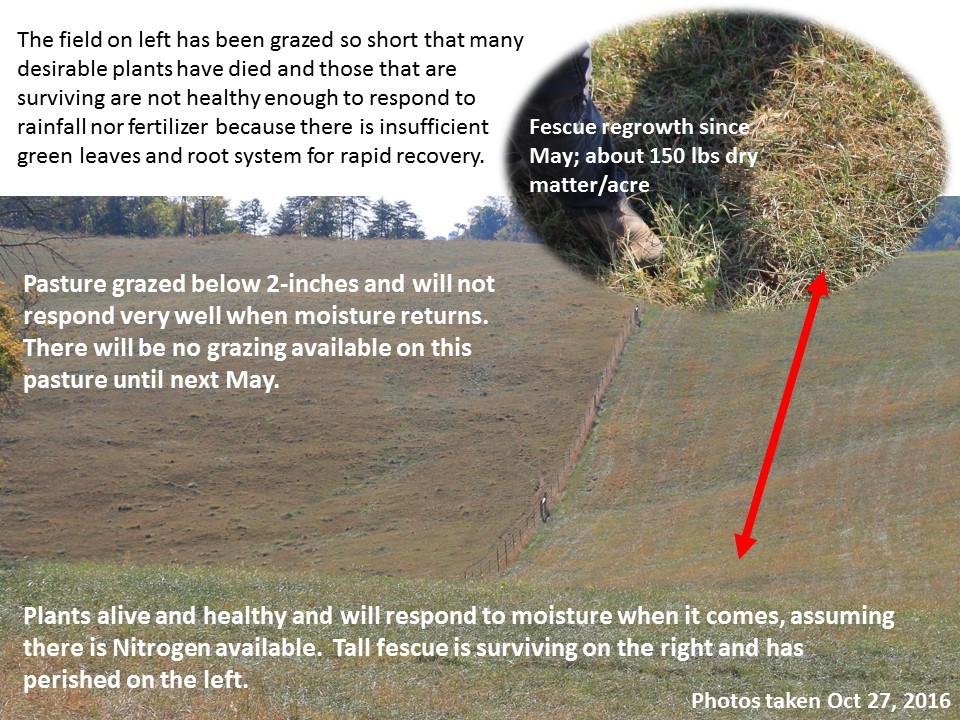

During droughts it is tempting to graze all pastures and to graze them short, however, short grazed pastures provide almost no feed and leaves many plants dead and others in such a weakened condition that they cannot respond well when conditions return. In the long run, it’s best to start feeding hay in a small portion of the farm any time grass is grazed to about 2-4 inches so that those plants will be in better health for regrowth following the stress period. Cattle cannot take enough bites in 12 hours of grazing to meet their needs when the pasture is less than about 3 inches height….so you may as well feed hay to meet their needs and protect the pasture.

The following considerations are based on the situation found on many livestock farms in East TN as of this week. Pastures have been completely used and hay has been fed for several weeks by many producers. The “surviving” vegetation in many pastures include bermuda, dallisgrass, grease grass (called purple top), broomsedge, nimble will, and various “weedy” types such as horsenettle, thistle, yellow crown beard, chicory. There is some possibility that tall fescue, orchardgrass and bluegrass will survive where they have not been grazed below 2-inches for long periods of time.

Considerations for the next few weeks that might help address short term feeding expenses and provide forage in late winter and early spring of 2017.

- Cull any cows that are not healthy or in poor condition or that are calving outside of a narrow calving window that fits with most of the herd.

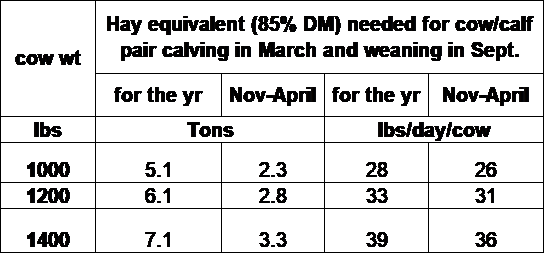

- Consider that it takes about 16-35 lbs of good hay per day to feed a dry cow, and it will take more nutrients to feed a nursing cow or growing animal. Review Table 1 for effects of cow size on feed needs (assuming suitable forage quality).

- If drought and overgrazing has left only warm season plants surviving there will be virtually no grazing until next May. This means 6-7 months of feeding stored feed at $1-$1.50/ head/ day, plus labor and fuel.

- Cattle prices are not likely to improve over the next few weeks/month therefore “holding on” for better prices is probably not a “good bet” in this situation.

- Sell weaned calves soon since prices have been dropping recently and are not likely to improve enough to cover additional feed cost that will be needed to keep them growing properly.

- If tall fescue or orchardgrass and bluegrass make up less than 50% of the pasture acreage, strongly consider no-till planting them as soon as possible, but before end of November. It is likely that 25-40 lbs N/acre will insure the seedlings can develop sufficiently this winter. Remember that the normal planting dates are before mid-October, but if you have no surviving cool season grasses it might be worth a “gamble” to get some acreage planted. Otherwise, there will be no cool season grasses on the farm next year. In most years, spring planting of cool season grasses is much more risky than planting in late fall. Do not plant annual ryegrass with these species as it will be very competitive and you will be “tempted” to graze it early next spring. Do not plan to graze any cool season grass seedlings until next April or May when it reaches more than 8 inches of growth.

- To have a significant chance for late winter-early spring grazing, consider planting small grains with annual ryegrass in pastures that are currently mostly covered with bermudagrass and dallisgrass or dead crabgrass or pasture with a thin stand of tall fescue. The odds are that one can expect 2000 to 4000 lbs of forage if good stands are obtained and Nitrogen rates are at 100 lbs/acre or so. This means adding 25-40 lbs of N next month and another 50-75 lbs/acre in March or April. Count the cost as compared to alternative feeds. Next fall August 15 to October 1 consider drilling in perennial cool season forages.

- The most consistent stands are usually obtained from drilling as compared to broadcasting on the surface of the soil, especially in the autumn-fall period. Seeding rates can usually be about 25-50% less when drilled as compared to broadcasting the seeds on soil surface. When planting late it is often worthwhile to plant slightly more seeds per acre as compared to planting “on time”.

- In the future consider the cost of re-establishing a pasture vs the start of feeding hay a few weeks earlier than normal. University budgets indicate costs ranging from $50 to $200 depending on the soil fertility status, and type of replanting and species being established. In addition, pastures that are less than 4 inches tall does not provide more than a 100-300 lbs of forage per acre that can actually be consumed ( this is less than 1/3 of a normal round bale of hay). In addition most cows will lose weight when forced to graze such short grazed pastures.

- Hay quality may be marginal in some cases, therefore it will be worth a few dollars to get a feed test to determine if supplemental energy or protein will be needed to meet animal requirements. As a general rule, energy will be the most limiting factor so be cautious about just using protein supplements without knowing composition of hay or other feeds.

- Corn gluten feed may be one of the most economical alternatives, especially since it has high protein and energy level. However, pay attention to the price per lb. of dry matter. Some by-products have significant amount of water in them.

- Graze residual growth in hay fields but do not graze below 2” in the winter. Remove cattle if pastures are prone to pugging (muddy and trampling of vegetation). Rationing standing grass with temporary fence will improve grazing utilization.

- Crop residues may be a good option if properly supplemented with energy and/or protein as needed. However, removing more than 50% of the residue from the cropland can result in soil erosion and much less water infiltration, which can result in more drought stress in the future.

Table 1. The effect of cow weight on forage needed for the year and winter feeding period.